:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Daruma Pilgrims Gallery

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

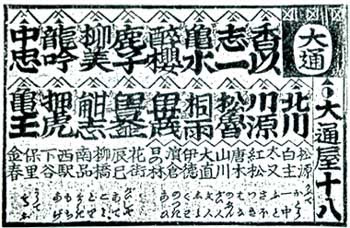

18 big spenders (juuhachi daitsuu)

十八大通

daitsuuya juuhachi 大通屋十八

The eighteen big spenders of Edo, the eighteen fashion leaders.

The great connosoirs, tsuujin 通人 (つうじん), tooribito とおりびと

The great playboys of their time.

The big 18 were the most famous of this group, most of them were the money-lenders of Kura-Mae.

How did they get sooo super-rich?

The Edo government got taxes in form of rice bushels and to convert them into pocket money, the servants of the government had to bring them to the exchange stores in Kura-Mae 御蔵前, a district with great rice store houses near the waterfront of Edo Bay. In good times, there were more than 70 of these merchants acitve.

They could buy rice when it was dirt cheap and used to sell it only when it was very expensive.

The profit they made was huge

© Photo: DANCHOUTEI 2007

These exchange stores were also big money lenders to the poor of Edo and took a good amount of intrest rates. So they were extremely rich and could freely spend their money, as a good "Child of Edo", edokko, would do.

Ooguchiya Jihei 大口屋治兵衛 was one of them. It is said he was the real original for the main character of the famous kabuki play SUKEROKU 助六. He had a special hairstyle and wore special cloths. Even his clogs (geta) were made of especially expensive wood.

Sukeroku Kabuki

. Sukeroku 助六 - Hero of Edo .

These rich merchants supported the Kabuki actors and theater, even learning shamisen and dance themselves and sometimes took part in the orchestra behind hidden windows.

Since they practised many forms of art themselves, the artists they sponsored were also of high quality.

They also supported other arts and crafts of Edo and spent a lot of their money in the pleasure quarter of Yoshiwara. The most expensive food and drink was just good enough for them and they were the most well-known gourmet of their time.

There is even a book about the foolish ways these 18 super-merchants spent their money.

Kuramae Baka Monogatari 蔵前馬鹿物語

One story is about one of these big spenders, who told people that whoever saw him kissing his girl during the next 30 minutes when he took a walk around Yoshiwara he would give him a thousand dollars. Which he payed on the spot! And kept kissing his girl and handing out money ...

Here is a ranking of these 18 famous spenders.

© Photo : www.kyosendo.co.jp

The people of Edo were fond of this kind of ranking, the most famous remaining still in our times is the ranking list (banzuke) of the Sumo ringers.

There were other rich merchants, trying to copy these playboy-patrons, but not knowing enough of the fine arts of high life. These imitators, nise tsuu ニセ通 were usually called "Young Master", waka danna 若だんな and rather the object of ridicule, especially in Rakugo Story Telling.

Back to the rich merchants.

The merchants from Kamigata, Western Japan, Osaka, Ise and other areas, on the other hand, where settled around the Nihonbashi area. They were also quite rich, but not such big spenders and the real Children of Edo thought of them as "stingy", kechi.

An old senryu says:

When the master of Iseya store buys first fish of the season, it will surely rain.

伊勢屋から鰹をよぶやいなや雨

First fish of the season was extremely expensive, and if he bought it, surely heaven himself would be surprized and start a shower.

. Iseya 伊勢屋 Iseya Store in Edo .

Takatsu Ihei 高津伊兵衛 / Iseya Ihei 伊勢屋伊兵衛 (Ihee)

Most of these merchants could not survive the modern times. But Mitsui, Sumitomo and Konoike of Osaka are still known today.

Japanese Reference

List of the famous Kuramae Fudasashi

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote

Fudasashi, Rice Brokers

Rice brokers, which rose to power and significance in Osaka and Edo in the Edo period (1603-1867) of Japanese history, were the forerunners to Japan's banking system. The concept actually originally arose in Kyoto several hundred years earlier; the early rice brokers of Kyoto, however, operated somewhat differently, and were ultimately not nearly as powerful or economically influential as the later Osaka system would be.

Daimyo (feudal lords) received most of their income in the form of rice. Merchants in Osaka and Edo thus began to organize storehouses where they would store a daimyo's rice in exchange for a fee, trading it for either coin or a form of receipt; essentially a precursor to paper money. Many if not all of these rice brokers also made loans, and would actually become quite wealthy and powerful. As the Edo period wore on, daimyo grew poorer and began taking out more loans, increasing the social position of the rice brokers.

Rice brokers also managed, to a great extent, the transportation of rice around the country, organizing the income and wealth of many daimyo and paying taxes on behalf of the daimyo out of their storehouses.

The rice brokers in Edo were called fudasashi (札差, "note/bill exchange"), and were located in the kuramae (蔵前, "before the storehouses") section of Asakusa. A very profitable business, fudasashi acted both as usurers and as middlemen organizing the logistics of daimyo tax payments to the shogunate. The rice brokers, like other elements of the chōnin (townspeople) society in Edo, were frequent patrons of the kabuki theatre, Yoshiwara pleasure district, and other aspects of the urban culture of the time.

Read more:

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

Yoshiwara

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Natsume Seibi 夏目成美

(1748 - 1826)

寛延6(1749)~ 文化13(1816)

He was a patron of Kobayashi Issa. He was born in a wealthy family in Kuramae. He studied haikai with his father and later learned by himself.

Kobayashi Issa 小林一茶

(June 15, 1763 - January 5, 1828) ISSA

Haiga by Nakamura Sakuo

Compiled by Larry Bole:

There are a surprising number of Seibi's (1748-1816) haiku translated into English. Independent of his relationship to Issa, which was based not only on a shared interest in haiku but also financial patronage, he was considered one of the three leading haiku poets of Edo during his day, along with Takebe Soochoo (1761-1814) and Suzuki Michihiko (1757-1819), according to Fumiko Y. Yamamoto, in an essay in the exhibition catalog, "Haiga: Takebe Soochoo and the Haiku-Painting Tradition".

Blyth says that Seibi's "verses have something innocent about them."

Yet Makoto Ueda, in "Dew on the Grass: The Life and Poetry of Kobayashi Issa," describes an incident involving Seibi and Issa in which Ueda describes Seibi, in spite of "being a gifted poet, [as also being] by profession a businessman who had amassed great wealth by dealing in rice and loaning money."

The incident occurred when Issa was staying at Seibi's house. "On the evening of November 28, [1810] [Seibi] went out to admire autumn leaves along the Sumida River, leaving [Issa] in the house along with the servants. The following morning Seibi discovered a considerable amount of cash was missing from his coffer. Issa, together with the servants, was forced to remain indoors for the next five days while an investigation was conducted. He was finally excused on Dedember 4, even though the money was not found. ..."

Ueda goes on to write, "The incident did not break up the friendship between the two, but it did give Issa another painful reminder of his need for steady income and a permanent home."

.................................................................................

霜がれや米くれろとて鳴雀

shimogare ya kome kurero tote naku suzume

frost-killed grass

"Gimme rice!"

a sparrow sings

According to Makoto Ueda, this haiku was written in January 1816 (Western calendar), shortly after the death of Issa's friend Natsume Seibi. Since Seibi often fed Issa, the hungry sparrow in the haiku could be the poet; Dew on the Grass: The Life and Poetry of Kobayashi Issa (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2004) 103. Ueda's date seems to be off.

The haiku appears in Issa's poetic journal Shichiban nikki in Twelfth Month 1816; _Issa zenshu^ (Nagano: Shinano Mainichi Shimbunsha, 1976-79) 3.457. This means, in the Western calendar, the date of composition would have been early 1817, not 1816. Dates in this archive follow the old Japanese calendar.

by Issa, 1816

(Tr. and Comment David Lanoue)

..........................................................................

. WKD : Kobayashi Issa 小林一茶 in Edo .

君なくて誠に多太の木立哉

kimi nakute makoto ni tada no kodachi kana

without you

truly, these trees

by Tada Temple

Tr. Chris Drake

This hokku was written late in the 2nd month (mid April) of 1817, about three months after the death of the Edo haikai master Natsume Seibi on 11/19 (January 6) in 1817. It's possible the hokku is a prayer on the hundredth day after Seibi's death, an important requiem day in Buddhism. Born in 1749 and fourteen years older than Issa, Seibi was one of the leading Edo haijin, and Issa sometimes linked renku with him. He was Issa's friend and also his patron, since he had inherited a successful wholesaling business. Seibi wrote in an objective, esthetic style that also included humor, but he didn't belong to any particular school of haikai, and he always enjoyed and encouraged Issa's unique, independent style.

Issa's requiem hokku is simple and restrained, suggesting more than it says. It seems to have been written at or while thinking about Seibi's hermitage, which Seibi called Hoorin-an (法林庵 Dharma Grove Hermitage). It was built next to the Tada Yakushi Temple near the eastern banks of the Sumida River in Edo. (See the picture at the link below.) The official name of the temple was Tookooji (東江寺), but it was popularly known as the Tada Yakushi Temple, since the main image at the temple was of the bodhisattva Yakushi, "master of medicine," and the temple was located in an area called Tada (多田), although in the hokku Issa uses the characters 多太 for Tada. Issa often visited the temple when he visited Seibi in his hermitage next door to the temple to take part in hokku or renku meetings, and he consistently writes 多太, a two-character word commonly used to represent "Tada."

Once in his diary Issa writes simply 多だ, using the phonetic kana character for -da. In the hokku, Seibi is now gone, though it is still hard to believe, and the hermitage is empty except for his followers and relatives. Just as Seibi stressed realism in his haikai, Issa now stresses that Seibi will never return, no matter how long the trees in the grove beside the temple remain standing around Seibi's house. Somehow the trees seem to realize Seibi has died and that they are now "without" him just as Issa is. When Seibi was alive the trees seemed more than trees, as if they were growing forms of the dharma (hoorin). Now they seem to be mere trees again, just as Issa at the moment feels he is less than he was when Seibi was alive. If Issa and the trees feel this, then the loss felt by many others who simply stand, suddenly surrounded by nothing, can perhaps be imagined.

R.H. Blyth published a translation of this hokku in A History of Haiku (1.385):

Without you, in truth

Too many and too wide

Are the groves.

Blyth made many very fine translations, but this is surely not among his best. Perhaps because he was writing before Issa's well-edited complete works came out, Blyth didn't seem to realize that Tada was the location of Seibi's hermitage, and he changed Issa's Tada (多太) to an abstract phrase using a different character, tadai no (多大の), 'great, much, many, vast.' Not only is this word not in the hokku, it radically changes the meaning, making the hokku hyperbolic and monumental. It also causes the middle line to have eight syllables. I think it's time for the reading tadai to be reconsidered unless new documentation can be presented to defend it. In this connection, it is very difficult to extend Blyth's interpretation by reading the characters for Tada (多太) as tadai (多大). These are separate words, and the characters 多太 are commonly used for the place name Tada, which occurs around Japan. Moreover, Issa himself consistently uses the characters 多太 to mean Tada. Both Issa's complete works (3.470) and the fine edition of Issa's Seventh Dairy by Maruyama Kazuhiko (2.303) read Issa's Tada (多太) as being a variant of the name of the Tada 多田 Temple, so there seems to be little doubt that Issa is writing about the modest grove of trees surrounding Seibi's hermitage beside the temple.

source : hokusetsu-hist.sakura.ne.jp

Here is a view of the Tada Yakushi Temple made in Issa's time. The hall with the image of Yakushi is toward the upper left in the right frame, and the bell tower is visible to the right in the left frame. The size of the grove of trees at the temple is pretty clear, though I don't know whether Seibi's hermitage was located to the left or the right of the temple grounds.

Chris Drake

There are also a few Tada Jinja in Japan. 多太神社

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Daruma and the Courtesans, Onna Daruma

芸者とだるま、女だるま

Storehouses, warehouses (kura, dozoo) ... and haiku

. Merchants of Edo - 豪商 gooshoo .

. kabunakama, kabu nakama 株仲間

merchant guild, merchant coalition

za 座 trade guilds, industrial guilds, artisan gulids .

Daruma Pilgrims in Japan

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

iki いき / イキ / 粋 / 意気 the CHIC of Edo

ReplyDelete.

Edokko (江戸っ子, literally "child of Edo")

.

Iseya 伊勢屋 Iseya Store

ReplyDeleteIseya Ihee 伊勢屋伊兵衛.

Ninben にんべん, Ihee Takatsu 高津伊兵衛 (1679 - )

.

http://darumasan.blogspot.jp/2006/09/yakimono-pottery.html

.