. The Class System of Edo .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

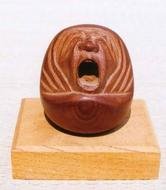

Daruma Pilgrims Gallery

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Eta and Burakumin

eta 穢多 (えた) "filthy mass" , burakumin

the "untouchables" of the Edo period

die Unberührbaren

burakumin (部落民, Literal translation: "small settlement people")

hamlet people

In the feudal era, the outcast caste were called eta (literally, "an abundance of defilement" or "an abundance of filth").

Some burakumin refer to their own communities as "mura" (村 "villages") and themselves as "mura-no-mono" (村の者 "village people").

They are a Japanese social minority group. The burakumin are one of the main minority groups in Japan, along with the Ainu of Hokkaidō, the Ryukyuans of Okinawa and the residents of Korean and Chinese descent.

The burakumin are descendants of outcast communities of the feudal era, which mainly comprised those with occupations considered "tainted" with death or ritual impurity (such as executioners, undertakers, workers in slaughterhouses, butchers or tanners), and traditionally lived in their own secluded hamlets and ghettos.

They were legally liberated in 1871 with the abolition of the feudal caste system. However, this did not put a stop to social discrimination and their lower living standards, because Japanese family registration (Koseki) was fixed to ancestral home address until recently, which allowed people to deduce their Burakumin membership. The Burakumin were one of the several groups discriminated against within Japanese society.

Other outcast groups included the

hinin (非人—literally "non-human") (the definition of hinin, as well as their social status and typical occupations varied over time, but typically included ex-convicts and vagrants who worked as town guards, street cleaners or entertainers. )

In certain areas of Japan, there is still a stigma attached to being a resident of such areas, including some lingering discrimination in matters such as marriage and employment.

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

. WKD : kojiki 乞食 beggar .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote

Kan Takayuki suggests that senmin were seen as religious people possessing a special talent which enabled them to interact with the mystical world. Some senmin were also called hafurinotami because they performed hafuri ritual duties. They were untouchable because of some ambiguous feeling involving both fear and reverence. Because of these special powers, senmin could have been a political threat to the Japanese Emperor, a living god and the master Shinto-priest who was supposed to have the same mystical powers. The symbolic power of the purity of the Emperor was enhanced by degrading the senmin class. The Emperor was in the highest position and the senmin were at the lowest in a kind of bipolar religious status.

In order to enhance the Emperor’s religious power, senmin were placed under the direct control of the Emperor or some other powerful clans.

Gradually the Shinto concepts of imi (taboo) and kegare (pollution) became linked to the Buddhist prohibition on taking any life.

source : www.iheu.org/untouchability

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

In rural Japan, small settlements and hamlets are also called BURAKU until nowadays.

I live in a hamlet with eight neighbour families, each in turn becomes the "hamlet head" (burakuchoo) for one year, even my husband, when it is our turn. This does not have any negative meaning.

The Class System of Edo

mibun seido 身分制度 (みぶんせいど) Klassensystem

At the end of the Edo period, there were about 6-7% samurai, 80-85% farmers, 5-6% merchants and craftsmen, 1.5% priests for Shinto and Buddhism and 1.6% Eta and Hinin.

shinookooshoo 士農工商 Shinokosho

the four social classes of

warriors, farmers, craftsmen, and merchants

source : blog.katei-x.net/blog

. WKD : The Class System of Edo .

. kyookaku 侠客 Kyokaku, "chivalrous Yakuza" .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Danzaemon 弾左衛門

- quote -

穢多頭 (eta-gashira) / 弾左衛門 (Danzaemon)

Danzaemon was the name taken by the head of the eta and other outcastes (including hinin and sarukai as well) in the Kantô region during the Edo period. The name is believed to have been passed down in a hereditary fashion, or at least to have been continuously held down through the generations.

The Danzaemon held some degree of direct authority (and responsibility) over the outcaste districts of the city of Edo, and of twelve surrounding provinces under his leadership, including the eight provinces of the Kantô, Izu, Kai, Suruga, and parts of Mutsu province, as well as a lesser degree of authority, and responsibility, over all the outcaste districts (buraku) throughout Japan.

The history of the position, or of the first man to hold it, are unclear, but it is assumed that the first Danzaemon was granted this role by the Tokugawa shogunate. The position seemed to have become definite by the mid-17th century, and from the mid-18th century onwards, the geographical extent of the Danzaemon's authority gradually expanded.

Thirteen men are believed to have held the title over the course of the Edo period, ending with Dannaiki, or Naoki, who was stripped of the role - and of the status, authority, and responsibilities associated with it - around the time of the Meiji Restoration.

- reference source : samurai-archives.com... -

弾左衛門とその時代

塩見鮮一郎

- reference : Edo Danzaemon -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote : From the Gutenberg Project

Tales of Old Japan

by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford

THE ETA MAIDEN AND THE HATAMOTO

Once upon a time,

some two hundred years ago, there lived at a place called Honjô, in Edo, a Hatamoto named Takoji Genzaburô; his age was about twenty-four or twenty-five, and he was of extraordinary personal beauty. His official duties made it incumbent on him to go to the Castle by way of the Adzuma Bridge, and here it was that a strange adventure befel him.

There was a certain Eta, who used to earn his living by going out every day to the Adzuma Bridge, and mending the sandals of the passers-by. Whenever Genzaburô crossed the bridge, the Eta used always to bow to him. This struck him as rather strange; but one day when Genzaburô was out alone, without any retainers following him, and was passing the Adzuma Bridge, the thong of his sandal suddenly broke: this annoyed him very much; however, he recollected the Eta cobbler who always used to bow to him so regularly, so he went to the place where he usually sat, and ordered him to mend his sandal, saying to him:

"Tell me why it is that every time that I pass by this bridge, you salute me so respectfully."

GENZABURÔ'S MEETING WITH THE ETA MAIDEN

When the Eta heard this, he was put out of countenance, and for a while he remained silent; but at last taking courage, he said to Genzaburô,

"Sir, having been honoured with your commands, I am quite put to shame. I was originally a gardener, and used to go to your honour's house and lend a hand in trimming up the garden. In those days your honour was very young, and I myself little better than a child; and so I used to play with your honour, and received many kindnesses at your hands.

My name, sir, is Chokichi. Since those days I have fallen by degrees info dissolute habits, and little by little have sunk to be the vile thing that you now see me."

When Genzaburô heard this he was very much surprised, and, recollecting his old friendship for his playmate, was filled with pity, and said, "Surely, surely, you have fallen very low. Now all you have to do is to presevere and use your utmost endeavours to find a means of escape from the class into which you have fallen, and become a wardsman again. Take this sum: small as it is, let it be a foundation for more to you." And with these words he took ten riyos out of his pouch and handed them to Chokichi, who at first refused to accept the present, but, when it was pressed upon him, received it with thanks.

Genzaburô was leaving him to go home, when two wandering singing-girls came up and spoke to Chokichi; so Genzaburô looked to see what the two women were like. One was a woman of some twenty years of age, and the other was a peerlessly beautiful girl of sixteen; she was neither too fat nor too thin, neither too tall nor too short; her face was oval, like a melon-seed, and her complexion fair and white; her eyes were narrow and bright, her teeth small and even; her nose was aquiline, and her mouth delicately formed, with lovely red lips; her eyebrows were long and fine; she had a profusion of long black hair; she spoke modestly, with a soft sweet voice; and when she smiled, two lovely dimples appeared in her cheeks; in all her movements she was gentle and refined.

Genzaburô fell in love with her at first sight; and she, seeing what a handsome man he was, equally fell in love with him; so that the woman that was with her, perceiving that they were struck with one another, led her away as fast as possible.

MORE is HERE

source : www.gutenberg.org

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Buddhists are not allowed to eat meat of animals with four legs.

The custom of eating meat from four-legged animals in Japan, especially beef, became more popular after the Meiji restauration.

Before modern times, beef was not eaten, only the hides of cows were used for drums and other items.

. WASHOKU - Eating Meat in Japan

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- quote -

Japan's hidden caste of untouchables

Mike Sunda

Japan has a reputation of being a homogeneous, mostly harmonious society. There are few foreigners, linguistic differences are rare and on the surface class distinctions are largely absent. But, as Mike Sunda discovered, there is one, often hidden, exception: Japan's untouchables.

In the corner of a pristine room tucked away in Tokyo's Shibaura meat market is a table topped with a stack of crudely composed hate mail - evidence of a prejudice that dates back to medieval times.

Slaughtermen, undertakers, those working with leather and in other "unclean" professions such as sanitation have long been marginalised in Japan. That prejudice continues to this day and especially for those working in the Shibaura abattoir.

Never mind that the men here are dicing up some of the most expensive and highly prized animals on the planet. This is where Japan's world famous wagyu beef is prepared - prime steaks, shot through with ribbons of fat, that can set you back eye-watering prices.

It's a process requiring such immense skill, training and mental fortitude that mastering the job can take a decade. And yet, for all the craftsmanship that goes into their work, many here will never speak freely about their occupation.

"When people ask us about what sort of work we do, we hesitate over how to answer," slaughterman Yuki Miyazaki says.

"In most cases, it's because we don't want our families to get hurt. If it's us facing discrimination, we can fight against that. But if our children are discriminated against, they don't have the power to fight back. We have to protect them."

Feudal origins

Like many in the abattoir because of his profession, Miyazaki is associated with the Burakumin, Japan's "untouchable" class.

Burakumin, meaning "hamlet people", dates back to the feudal era. It originally referred to the segregated communities made up of labourers working in occupations that were considered impure or tainted by death, such as executioners, butchers and undertakers.

The lowest of these outcasts, known as Eta, meaning "abundance of filth", could be killed with impunity by members of the Samurai if they had committed a crime. As recently as the mid-19th Century a magistrate is recorded as declaring that "an Eta is worth one seventh of an ordinary person".

Though generally considered offensive, the term Eta is still in use today. One of the letters received at the abattoir expresses sympathy for the animals being killed "as they're being killed by Eta."

The caste system was abolished in 1871 along with the feudal system. Yet barriers to their integration remained. Marginalised Burakumin communities were widespread across Japan.

Having the wrong address on your family registry, which records birthplace and is often requested by employers, often led to discrimination.

Efforts were made in the 1960s to improve their lot by funding assimilation projects that improved housing and raise living standards, but despite this discrimination continued..

Blacklist

In the mid-1970s, a Buraku rights group discovered the existence of a 330-page handwritten list of Buraku names and community locations that was being sold secretly to employers by mail order.

Many big name Japanese firms were using the list to screen job applicants.

As recently as 2009, there was public outcry when Google Earth incorporated publicly available historical maps of Tokyo and Osaka that pinpointed the location of Buraku villages in feudal times, dragging up the contentious issues of prejudice and profiling.

Today, the exact number of people living in historic Buraku communities is hard to pin down.

A government survey in 1993, listed nearly a million people living in more than 4,000 communities around the country. The Burakumin Liberation League (BLL), a rights organisation founded in 1955, puts the number of communities at around 6,000 and estimates that the total number of Burakumin is closer to three million.

Toshikazu Kondo, from the BLL, says they still encounter such lists today, but find that they are being used for different purposes.

"When it was discovered in the 1970s that corporations were using these lists to conduct background checks on potential recruits, regulations were brought up to make that illegal," he says.

"Nowadays it's still a well-known fact that people are buying this information, but rather than corporations, it's individuals buying it to check on future in-laws ahead of marriage. That's one of the biggest examples of discrimination that we frequently face."

The mob connection

In a survey last year conducted by the Tokyo government, one in 10 said that they would have reservations about their child marrying someone with Burakumin ancestry, although nearly a half of respondents said this wouldn't bother them.

One reason for the lingering stigma may be the association of Buraku communities with the yakuza, the Japanese mob.

Jake Adelstein, an American reporter who has worked the Japanese crime beat for 20 years, estimates that a third of yakuza come from Buraku communities, drawn to the organization when other doors were closed to them.

A yakuza leader justified his organisation to Adelstein on the basis that it gave people who had suffered discrimination a family and discipline.

"It's true - the yakuza is a meritocracy," Adelstein says. "If you are willing to be ruthless and a bully and pledge your loyalty to your boss, they'll take you."

However, it's not just those with Burakumin ancestry that run the risk of prejudice. So strong is the historic connection between certain jobs and this historical category of outcasts that all workers at the slaughterhouse run the risk of discrimination, no matter their family history.

Beer snub

Yutaka Tochigi, the 58-year-old president of the Shibaura Slaughterhouse Union left his job as a computer programmer to spend more time with his children but immediately ran into opposition from his family.

"My father said to me that I might as well be pumping septic tanks. I realised that he meant I was doing a Burakumin job," says Tochigi, who doesn't have Burakumin ancestry.

"I remember once when my wife and I were visiting with some of her father's relatives. When I told them what I did, they stopped pouring me beer."

Both Tochigi, and the BLL's Kondo are, however, hopeful that things are changing for the better.

"You don't see as much hate speech as before - and those who have attempted it have been forced to pay damages in court cases," Kondo says.

"We still hear about workplace discrimination and anti-Burakumin graffiti, but more than ever before there are people getting in touch to inform us when this happens."

The small room which contains the table display of hate mail is part of the Shibaura meat market's information centre, an educational outreach effort to try and change attitudes.

Just next to the table, on a wall, are letters of another kind. Grateful messages from groups of schoolchildren brought in on tours to learn about the remarkable skill and dedication with which the labourers carry out their jobs - evidence, perhaps, that old, discriminatory habits may yet be consigned to history.

- source : Mike Sunda -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Haiku by Kobayashi Issa

えた村の御講幟やお霜月

eta mura no okoo nobori ya o-shimotsuki

in the Eta village

there is a Buddhist banner -

this frost month

Frost Month (shimotsuki)

the eleventh lunar month, now November

. . . . .

えた町も夜はうつくしき砧哉

eta mura mo yo wa utsukushiki kinuta kana

in the outcasts' village too

a lovely night...

pounding cloth

. kinuta 砧 (きぬた) fulling block

. . . . .

えっ太らが家の尻より蓮の花

ettara ga ie no shiri yori hasu no hana

outcastes' houses --

behind them nothing but

lotus blossoms

Tr. Chris Drake

This hokku is from the 6th month (July) of 1822. I take it to be a strongly positive hokku indicating that Issa feels this outcaste village beside a pond or lake is paradoxically able to give humans in general a vision of the Pure Land on earth. The so-called Eta or "Much Filth" class was the lower of the two outcaste classes in Issa's time, placed below the Hinin or "Non-Human" class, which was not hereditary and which could sometimes be escaped from. The Eta or Ettara, the colloquial term used by Issa, were considered by the authorities and most people to be not only unclean but somehow spiritually "polluted," and after the establishment of the shogunate, they were rigidly separated from the rest of society and forced to live in ghetto-like villages or areas of towns and cities. The standard legal formula was that the life of one ordinary person was worth the lives of seven outcastes. Forbidden to farm, they were forced to do "dirty" jobs that were generally looked down on, such as hunting, butchering, tanning, leatherworking, cremation, gravedigging, public sanitation work, low-level police work, and guarding and executing prisoners. They also did gardening and landscaping, though that hardly seems "polluting."

Five hokku earlier in his diary, Issa uses the traditional Buddhist image of the "lotus in the mud," and in this hokku as well he implicitly invokes purity amid filth and mud, though in a somewhat unusual way. This is because, I think, he knows that Shinran, the founder of the True Pure Land school of Buddhism, refused to use the name Eta and spoke only of "those who had done bad deeds" -- a class of people he eventually expanded to include all of humanity in the present age, though he knew most people didn't want to admit their membership. Since no humans are perfect, Shinran asserted, it is those who have admitted to doing bad deeds who are most loved by Amida, since they are existentially dependent on Amida to guide them to the Pure Land and believe in Amida with a degree of sincerity and intensity that people who seek to improve their karma by themselves by doing good are unable to feel. As Issa also knew, the overwhelming majority of outcaste families believed in Amida and prayed at a True Pure Land "Eta temple" nearby or in the midst of the ghetto. If Shinran had been alive in Issa's time, when discrimination was minutely codified and ghetto boundaries were more rigid than in Shinran's time, he would probably have praised outcaste communities highly as being deeply loved by Amida. In contrast, the True Pure Land upper clergy in Issa's day mostly cooperated with the shogunate in its policy of strictly segregating the outcastes.

It is Shinran's view that Issa seems to hold: the fronts of the rundown houses in the village are not imposing, but what spreads out behind them is. The houses are near the edge of the water, and behind them stretches out a pond covered with lotus blossoms. The contrast is strong, and the sight beyond the back of the houses is transcendent, so I take Issa to be suggesting that the people in the village, with whom he has probably spoken a bit, have in their own way come close to discovering the Pure Land on earth, although most people in the "ordinary" world, with their mud-spattered eyes, see only "filthy," untouchable people in the village. By implication, the mud in the traditional Buddhist metaphor is the rigid class system which treats some of the most devout and sincere believers in the land as nothing more than unclean semi-humans. The outcastes' houses seem to mark the border separating not only front from back but appearance from reality, and the true spiritual level of the villagers, though many of them are forced by their jobs to kill and skin animals or break other Buddhist injunctions, is something lotus-flower-like that can give a careful observer like Issa a temporary vision of what the Pure Land must be like.

Three years earlier, in the 5th month (June) of 1819, another version of this vision appears:

koukou to eta ga yajiri no shimizu kana

how far it spreads,

the pure water behind

the outcastes' houses

If you take the trouble to look beyond the front of the outcastes' houses, you can see an expanse of pure water just beyond them that seems to suggest to Issa the clear water said to flow in the Pure Land. A pure spring seems to flow into a pure pond that seems to spread out with no limit in sight. Perhaps the feeling of width, almost vastness (koukou), comes from the purity and naturalness Issa feels in the devout outcaste people who live there. They must seem more sincerely open to Amida than most people he meets.

Chris Drake

七夕やよい子持たる乞食村

tanabata ya yoi ko mottaru kojiki-mura

star festival --

in the beggar village

they're all good kids

Tr. Chris Drake

This early autumn hokku was written in 1826, probably in the 7th month (August), a month before Issa married his third wife. Issa's only surviving child, a girl, was born after he died. A version in a letter sent by Issa during this month has the second line as: yoi ko mochitaru.

Issa doesn't use the word, but he seems to be talking about a ghetto village for people of the Hinin outcaste class. Unlike the Eta outcaste class, the Hinin class was not hereditary, though it was hard to get out once you were in it. It was composed mostly of people who had committed what were considered moderately serious crimes, with incest being one of the most common, along with people who could not support themselves and who no longer had relations with any relatives or were alone and sick or were runaways from their families. Many had become beggars, but the authorities didn't allow independent beggars.

Ordinary beggars were forced to join a Hinin ghetto in a city or a segregated village in the country, as in this hokku. Each ghetto had a headman with many assistants, and they negotiated with the local authorities and found work for able members, who did various cleaning and public sanitation jobs as well as working as low-level policemen and prison workers, etc. They did many of the same jobs that Eta did, such as leatherworking, but they were more vulnerable to being laid off, since they didn't have traditional guild rights, as the hereditary Eta class did. Actors and street performers were good examples of Hinin who were sometimes able to make enough money to rise out of the Hinin class. Those who were weak or had no skills, however, continued to be beggars, with the difference being that they had to get permission from and report their earnings to the local Hinin boss.

Issa seems to have visited a Hinin village near his hometown at the time of the 7/7 star festival, known as Tanabata. In his various hokku about outcastes, Issa often stresses that there is no basic difference between outcastes and non-outcastes, and this hokku is no exception. The children of the village must be playing games all day and night and making festival decorations and shapes from paper or straw, and those of them who can write with a brush express their wishes on strips of paper that they hang from the limbs of small bamboo trees that stand in front of people's houses. The children know the legend about this night, according to which the weaving woman star and the oxherd star, normally separated by the Milky Way, will be able to meet once a year on this night if clouds don't cover the sky, and perhaps they worry as kids will about what will happen to the lovers if it rains.

To Issa the kids in the village show just as much creativity and give off just as much positive energy as kids do in every other village, and he seems to be grateful for festivals like the star festival, when the social distinctions of a rigid class system can be mostly ignored, at least temporarily. Issa's use of yoi, 'good, nice, superb,' covers a wide range of meanings, but probably at root he is stating that all human beings are born good, even if some may be burdened with restrictions due to social class, poverty, or karma (though Issa usually isn't a strong karmic determinist, since the compassion and love of Amida and the believer are stronger than karma). Probably Issa is hoping that many of these children will use their best instincts to escape from the Hinin class when they get a little older. Issa himself surely feels kinship with the children, since he signed the preface to a collection of his work in 1811, the My Year's Collection (Waga haru shuu), with the name "Issa, Boss of the Beggars of Shinano."

The picture shows boys in Issa's time writing wishes or perhaps simple poems that they will tie to the limbs of a cut bamboo tree, which serves as a ritual decoration linking earth and heaven.

Chris Drake

. Tanabata 七夕 Star Festival .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

shizu 賎(しず)身分の低い者 a person of low standing,

meeserly, vulgar, despicable

vulgar, mean ...

of low social status 身分・社会的地位が低い

poor mazushii 貧しい。misuborashii みすぼらしい

賎 (also as adverb iyashii )

senmin 賎民 (賤民) humble [lowly] people [folk]

despise people (as opposed to the ryoomin 良民, the good citizens)

Pöbel; Gesindel; Lumpengesindel; Plebs ; Canaille.

sogar die Unberührbaren

gesen no tami 下賤の民 people of low birth, humble origin

. . . . .gemin 下民

kawaramono 河原者 "people living at the banks of rivers"

(including travelling actors)

People were also divided into 5 subgroups

ryooko 陵戸・ kanko 官戸・ kenin 家人・kumehi 公奴婢・ shimehi 私奴婢

mehi, dohi 奴婢 means servant

Knecht; Gesinde; Hörige ; Diener.

. . . . .

鬼は賎の目に見えない

oni wa shizu no me ni mienai

demons are not visible to lowly people

. . . . .

花は賎の目にも見えけり鬼薊

hana wa shizu no me ni mo mie-keri oni azami

these flowers can be seen

even with the eyes of lowly folks -

demon thistles

Matsuo Basho

Tr. Gabi Greve : Thistle Haiku

Read a discussion of this haiku.

.................................................................................

賎の子や稲摺りかけて月を見る

shizu no ko ya ine surikakete tsuki o miru

this child of low folks -

after husking rice

it looks at the moon

Tr. Gabi Greve

Peasant children

hull rice

gazing at the moon.

Tr. Thomas McAuley

A peasant’s child

husking the rice, pauses

to look at the moon.

Tr. Makoto Ueda

Husking rice,

a child squints up

to view the moon.

Tr. Lucien Stryk

A farmer’s child

hulling rice arrests his hands

to look at the moon.

Tr. Nobuyuki Yuasa

a poor peasant boy

husking rice, he pauses now

to gaze at the moon

source : www.tclt.org.uk

We have the same kanji 賤 in this word

. yamagatsu 山賤(やまがつ) woodcutters

lumberjacks

Read this entry with another haiku by Matsuo Basho.

- Kashima Kikoo 鹿島紀行 - A Visit to the Kashima Shrine -

. Matsuo Basho 松尾芭蕉 - Archives of the WKD .

MORE - kodomo 子供 child, children -

. Matsuo Basho 松尾芭蕉 - Archives of the WKD .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Daruma Pilgrims in Japan

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO TOP . ]

- #eta #burakumin #danzaemon -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

9 comments:

In through the bombed-out window

a leaflet floats.

This in our modern times...

Women, men, children

drumming out the bandits --

percussion pots and pans

Saša Važic

http://europasaijiki.blogspot.com/2010_03_01_archive.html

Gabi san thank you for your kind comment on Eta.

Your explanation is very understandable.I was born before World War in country side, so I know well about Eta and discrimination in daily life.

Your reference is perfect, I think you wrote this item on the base of your real feeling.

You have done good achievement.

sakuo.

There's quite a few translations there, Gabi. Very interesting to review them and ponder.

D.

I wondered if the honorable prefix "O" placed before the Frost Month in Issa's ku might not represent a humble way of speaking among burakumin (Issa does not waste syllables to fill space) and checked in case it might be a word, itself and it was! Oshimotsuki is not just the Frost-month but the week (11/22-28) before Shinran's Death Day says the Dict.goo; but according to Google's main page, said Day is Jan 16, so you will have to figure that all out before adding a note re the ku! 敬愚 robin

Ref. Dict.goo 浄土真宗で、11月22日から親鸞(しんらん)の命日の28日までの期間。法要が営まれる。お七夜。

hatamoto 旗本 samurai class

A direct retainer of the Tokugawa Shôgun. "bannerman"

.

Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford アルジャーノン・フリーマン=ミットフォード

1st Baron Redesdale, (1837 – 1916)

.

Tales of Old Japan (1871)

DIJ Tokyo paper on Edo era discrimination; OPEN ACCESS

http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/cj.2013.25.issue-1/cj-2013-0002/cj-2013-0002.xml

- - - - -

A Brief History of Buraku Discrimination in Japan, By Tim Boyle

Buraku Liberation Center, United Church of Christ in Japan, Osaka, Japan

http://ems-online.org/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/history_of_buraku_discrimination.pdf

.

BOOK

Performing the Buraku

By Flavia Cangià

.

(Freiburg Studies in Social Anthropology / Freiburger Sozialanthropologische Studien)

.

at amazon com

and as google-book to read

.

Legend from Nagano

.

. bookon 亡魂と伝説 Bokon Legends about a dead soul .

Once the villagers were having a meeting in the evening, when suddenly they heard someone cry outside the window.

There were two naked men standing outside.

When the villagers chanted the Amida Buddha prayers, the men disappeared.

The two men were butchers, but because of their work they could not get any kechimyaku 血脈 linage charts.

When 閑唱上人 Saint Kansho came to 穢多村 the Eta village and gave them Kechimyaku.

The two appeared in his dream, thanked him and then disappeared.

.

https://heianperiodjapan.blogspot.com/2020/04/kechimyaku-lineage-legends.html

.

Post a Comment