:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Fudo Myo-O Gallery

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Nio, Deva Kings 仁王 (Nioo, Niou)

The Nio (Benevolent Kings) are a pair of protectors who stand guard outside the temple gate at most Japanese Buddhist temples, one on either side of the entrance. In Japan, the gate itself is often called the Nio-mon (literally Nio Gate). Their fierce and threatening appearance wards off evil spirits and keeps the temple ground free of demons and thieves. In some accounts, the Nio were said to have followed and protected the historical Buddha when he traveled throughout India. They have since been adopted by the Japanese into the Japanese Buddhist pantheon.

Each is named after a particular cosmic sound. The open-mouthed figure is called "Agyo," who is uttering the sound "ah," meaning birth. His closed-mouth partner is called "Ungyo," who sounds "un" or "om," meaning death. Other explanations for the open/closed mouth include:

(1) mouth open to scare off demons, closed to shelter/keep in the good spirits;

(2) "Ah" is the first letter in the Sanskrit alphabet and "Un" is the last (same in Japanese syllabary too), so the combination symbolically represents all possible outcomes (from alpha to omega) in the cosmic dance of existence.

Read all the details in English here:

Nio Protectors of Japan - Mark Schumacher

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Akagami Nio-O 赤紙仁王 Nio covered in red paper

東覚寺 - 東京都北区田端 2-7-3 Tokyo, Tabata

source : facebook

Gofunai Henro PIlgrims

. Nr. 66 - Toogakuji 東覚寺 Togaku-Ji

- 白龍山 Hakuryuzan 寿命院 Jumyo-In 東覚寺 Togaku-Ji

北区田端2-7-3 / Kita ward, Tabata, 2-7-3 .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The most famous rendering of A-Un are probably the huge statues of the Nioo-Deities of the gate of the temple Todai-Ji (Toodai-Ji 東大寺).

These huge statues are placed with a lot of empty space above them. The sunrays reaching the gate will be reflected on the billowing robes and finally reach the face of each deity in an outburst of cosmic energy above their heads.

The statue A (阿形 agyoo) has his mouth open, the beginning of all things.

The statue UN (吽形 ungyoo) has his mouth shut, the end of all things.

Aum A-Un, (阿吽) Om ... and Haiku

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Nio-Mon, the temple gate with two guardian deities

仁王門と仁王力士像 / 二王門

These gates usually have two stories and in the lower part, behind wooden lattice, are the statues of the Deva Kings (kongooza 金剛座), facing toward the onlooker as he enters the temple compound and showing their angry face at all enemies of Buddhism.

There are very few temples where these Deva Kings face each other. In this case, then you stand inside the gate, they seem both to look at YOU rather sternly, asking to leave your negativity and bad thoughts all outside and cleanse your mind before going inside.

Asakusa Kannon in Tokyo 浅草観音

Kaminari Mon (Thunder Gate) with Nio Statues and Haiku

Sometimes people chew a piece of red or white rice paper, press it on a part of their body that hurts and then throw it at the deity in the gate. If the paper sticks to the right place of the deity, the person will be healed.

If children manage to climb through between the legs of these statues, they will grow up healthy and fast runners.

These deities have also been venerated for their speed, especially with the running post curriers of the Edo period (hayabikyaku 早飛脚(はやびきゃく)). Even now we find many straw sandals hanging at these gates.

Temple Saikoku-Ji : My Daruma Haiku

Most of the old statues are rather damaged, since they have to withstand the weather of all seasons. Hence the one haiku by Kikaku.

Their strong physical features might go back as far as the Greek deity Hercules.

The clay statue of Mighty Diamond Deity, Shitsu Kongo Yasha (see stamp below) from 733 at the Sangatsu-Do Hall of the Todai-Ji temple compound is most famous. It has been kept a "secret statue" (hibutsu) inside and is therefore well preserved to our day.

External Link:

Yamadera, where Basho composed his famous shizukesa ya

Risshakuji's Nio-mon (Deva Kings Gate)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

© Menuki sword decoration, from Robert Roemer, 2007

Click the photo for the LINK.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Nioo mata kuguri 仁王尊股くぐり

During the three days of the New Year celebrations and at the big temple festivals in Spring and Autumn it is possible to crawl under the legs of the Nio statues, which is another special ritual not seen in Japan. It will ward off evil influence and kept you healthy, especially in times of smallpox in the Edo period.

It used to be a custom of local people, mostly bringing their sick children.

But later it spread and even Daimyo lords came to perform this ritual.

. Temple Manman-ji (万満寺 - 萬満寺) .

Matsudo, Chiba 千葉県松戸市馬橋

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Kurama yama no a-un-tora 鞍馬山のあうん虎 A-Un tigers

. Tora トラ - 虎 - 寅 Tiger Toys .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Deutsch / German

Nioo (Kongoo Ten; Vajrapaani)

Torwächter-Recken.

Wenn die Gottheit Shitsu Kongoo Shin (Shikkongoo Shin, Shukkongoojin; Kongoo Rikishi, siehe unten) sich in zwei Körper spaltet, entstehen zwei Nioo-Figuren.

Zwei Wächtergestalten als Torwächter am Haupttor (Nioomon, Sanmon) eines Tempels. Rechts an der Ostseite Naraen Kongoo Ten mit offenem Mund (AH-Figur (agyoo), einatmen, Licht, Anfang aller Dinge) und links an der Westseite Misshaku Kongoo Ten mit geschlossenem Mund (HUM-Figur (ungyoo), ausatmen, Schatten, Ende aller Dinge).

Gewähren Gesundheit und Körperkraft. Man kaut ein Stück weißes oder rotes Papier, legt es auf die kranke Stelle des Körpers und wirft es dann auf die Statue eines Nioo. Wenn das Papier an der richtigen Stelle hängenbleibt, wird die Krankheit geheilt.

Diese Gottheiten wurden früher auch von den schnellfüßigen Postkurieren verehrt, daher hängen viele Strohsandalen an den Holzgittern. Riesige Strohsandalen von der Länge der Figuren selbst hängen z.B. am Nioomon des Tempels in Asakusa in Tookyoo. Es gibt auch Nioo-Paare vor anderen Tempelhallen.

Die ältesten Statuen stammen aus dem 8. Jahrhundert; sie sind meist aus Holz gefertigt und daher heute oft stark beschädigt, da sie immer im Freien stehen, rechts und links am Tor in holzvergitterten Kammern (kongooza).

Die beiden großen Nioo von Unkei und Kaikei im Sanmon des Tempels Toodaiji in Nara stehen mit den Gesichtern zueinander. Über ihnen ist ein großer, leerer Raum, in dem sich ihre Kraft konzentriert. Sie sind so gestaltet, daß die einfallenden Sonnenstrahlen sich an verschiedenen Stellen der Statue brechen und schließlich nach oben wirbeln.

Ikonografie:

Stehende Figuren mit gespreizten Beinen. (Wenn kleine Kinder zwischen den gespreizten Beinen durchlaufen, werden sie kräftig und gesund.) Nackter, muskulöser Oberkörper; mit furchterregendem Gesichtsausdruck und wehenden Schals. Haare in einem Knoten auf dem Haupt zusammengebunden. In der Hand einen einzackigen Donnerkeil bzw. einen Schatz-Stab. Dieser Donnerkeil war oft aus einem anderen Material als die Hauptstatuen und ist daher heute meist verloren.

...................................

Kongoo Rikishi oder Shitsu Kongoo Shin

(Vajradhara, Vajrapaani)

金剛力士

"Diamant-Recke". Träger des Diamant-Szepters. Oft zwei Statuen als Nioo-Torwächter, rechts Kongoo Rikishi, links Kongoo Misshaku. Sein Bruder ist Bonten.

Möglicherweise abgeleitet aus der historischen Gestalt des Cousins von Shakyamuni, Devadatta, der zunächst den Buddhismus bekämpfte, sich aber dann bekehrte und zu seiner Schutzgottheit wurde.

Die reckenhafte Gestaltung dieser Figuren leitet sich möglicherweise aus griechischen Statuen des Herkules ab.

Gewaltige Schützer des buddhistischen Dharma. Eigentlich nur ein Dämon mit einem Donnerkeil, in diesem Fall "Mächtige Diamant-Gottheit" (Shitsu Kongoo Shin 執 金剛神) oder "Mächtiger Diamant-Dämon" (Shitsu Kongoo Yasha 執 金剛夜叉) genannt. Besonders bekannt ist die um 733 entstandene, gewaltige Ton-Statue im Sangetsudoo des Tempels Toodaiji in Nara mit chinesischer Rüstung und wehenden Schals. Nach Norden gewandt bewacht er die Hauptgottheit. Diese Statue wurde lange Jahre als "Geheim-Buddha" versteckt gehalten und ist daher noch sehr gut erhalten.

Ikonografie:

Flammende Haarfrisur oder Knoten auf dem Haupt.

Oberkörper nackt, mit furchterregendem Gesichtsausdruck. Wehende Schals um die muskulösen Arme. Nackte Füße.

© Gabi Greve

Buddhastatuen (Buddha statues) Who is Who

Ein Wegweiser zur Ikonografie von japanischen Buddhastatuen

"Mächtige Diamant-Gottheit"

(Shitsu Kongoo Shin 執 金剛神)

. Shitsu Kongo Shin 執金剛神 - at Nara .

東大寺法華堂

and Taira no Masakado 平将門 / 平將門

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

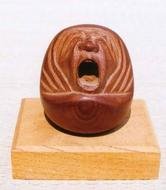

A-Un Daruma 阿吽 だるま

CLICK for more photos !

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

.................. H A I K U

からびたる三井の仁王や冬木立

karabitaru Mii no Nioo ya fuyu kodachi

Kikaku 其角

all dried out

the Deva Kings' statues at Mii temple -

trees in winter

Tr. Gabi Greve

More about this haiku is here

Mii Temple 三井寺(園城寺)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

かはほりや仁王の腕にぶら下り

kawahori ya Nioo no ude ni burasagari

Look at the bats!

They dangle down from

the arms of the deva king!

Kobayashi Issa

Tr. Gabi Greve

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

花の坂登りて仰ぐ仁王像

hana no saka noborite aogu nio zoo

slope with cherry blossoms

climbing up, looking up

at the Nio Statues

iriba 入葉

Tr. Gabi Greve

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

仁王像虹出てもまだおこってる

nioo zoo niji dete mo mada okotteru

Nio Statues -

even as a rainbow appears

they look angry

When Kaori, a six-grader, visited the temple, these statues seemed to show an angry face to her. Even as a rainbow started to show and she felt happy, this expression did not change.

Kaori 小6 玉望かおり

Tr. Gabi Greve

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Ishiteji 石手寺 Ishite-Ji - "Stone Hand Temple"

仁王門 Nio-Gate

Nr. 51 of the Shikoku Pilgrimmage

春風や 遍路飯くふ 仁王門

harukaze ya henro meshi kuu Niomon

spring breeze -

pilgrims eating rice

at the Nio Gate

Shikoku Pilgrimage (henro) and Haiku

. Emon Saburoo, Emon Saburō 衛門三郎 Emon Saburo .

and the legend about the name "Stone Hand".

Ishite-ji (石手寺) is a Shingon temple in Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture, Japan. It is Temple 51 on the Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage. Seven of its structures have been designated National Treasures or Important Cultural Properties.

- - - More in the WIKIPEDIA !

source : facebook

What's unique about this Fudo is that it can only be found in the dark cave behind Ishite-ji in Matsuyama. There are many different statues, so you have to use a flashlight to obtain clarity.

- shared by Bradford on facabook

. Fudō Myō-ō, Fudoo Myoo-Oo 不動明王 Fudo Myo-O

Acala Vidyârâja - Vidyaraja - Fudo Myoo .

. Iyo 12 Yakushi Temples, Shikoku 伊予十二薬師霊場 .

Anyooji 安養寺 Anyo-Ji / 松山市二神甲 640

now known as 石手寺 Ishite-Ji

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

ah...ummm...

I hesitate before passing

the Deva Kings

Earl Keener

The Narrow Roads of Ehime

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Not to mix it with

Grebe (Podiceps family of Birds), Nio Bird

Kaitsuburi, nio カイツブリ ニオ and Haiku

Hassaku Doll Festival at Nio Village

仁尾八朔人形祭り and Haiku

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. Legends and Tales from Japan 伝説 - Introduction .

.......................................................................

Oita 大分県 国東町 Kunisaki

The Nio from India (唐天竺 Kara Tenjiku, China and India ) wanted to compare this powers with Shomen Kongo and went over to China for a match. But he could not win and had to flee further, until he finally came to Japan. Kongo came after him and Nio had to hide somewhere in Japan, so he made it to a temple and stayed at the gate.

. Shōmen Kongō 青面金剛 Shomen Kongo .

.......................................................................

- source : nichibun yokai database -

31 to explore

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::