:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Daruma Pilgrims Gallery

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Tosa Mitsuoki 土佐光起

Self-portrait, 1679

Painter

November 21, 1617 – November 14, 1691

"Do not fill up the whole picture with lines;

also apply colors with a light touch.

Some perfection in design is desirable.

You should not fill in more than one third of the background.

Just as you would if you were writing poetry,

take care to hold something back.

The viewer, too, must bring something into it.

If one includes some empty space along with an image,

then the mind will fill it in."

.................................................................................

Tosa Mitsuoki was the successor of the Tosa school after his father, Tosa Mitsunori (1583–1638).

Mitsuoki brought the Tosa school to Kyoto after around 50 years in Sakai. When the school was settled in Sakai, Mitsunori painted for townsmen. The school was not as prolific as it once was when Mitsunobu, who painted many fine scrolls (1434–1525) ran the school. Mitsuoki moved out of Sakai with his father, in 1634 and into the city of Kyoto. There, he hoped to revive the Tosa school to gain status back into the Kyoto court.

Around the time of 1654 he gained a position as court painter(edokoro azukari) that had for many years traditionally been held by the Tosa family, but was in possession of the Kano school since the Muromachi period (1338–1573).

Reclaim to fame

In 1654, Mitsuoki restored fortunes back to the family school when he earned the title of the edokoro azukari, which means “head of the court painting bureau”. Now the Tosa school was back into the highlight of the court. The school prospered throughout the Edo period, during the years of 1600 to 1868. Mitsuoki can be considered as the last groundbreaking painter of the Tosa school. He was succeeded by a long line of painters, starting with his son, Mitsunari (1646–1710).

Many of the successors used the same techniques and syle of painting as Mitsuoki, which slowly over the years of the duration of the Edo period, the works became repetitive. The lack of innovation produced many scrolls that could be seen as done by Mitsuoki himself. Another school in effect around the same time called the Kano school, flourished just as the successors of the Tosa school.

Mitsuoki was known for reintroducing the Yamato-e style. Yamato-e (大和絵) is a style of ancient Japanese painting inspired by paintings in the Tang dynasty.

His Works

Kitano Tenjin engi emaki - a picture scroll depicting the chronicle of the Kitano Shrine)

Itsukushima Matsushima zu-byōbu - Picture Screens of Itsukushima and Matsushima

Kiku jun zu - A Quail and Chrysanthemums

Quail and Millet Screen

Ono no Komachi – Ink and color on silk, hanging scroll

Quail and Poem

The Tosa School

The Tosa school, in its own history, expressly stated that the school founded in the ninth century owed nothing to the influence of China. But the style of the Tosa school looks like it is was greatly influenced by Chinese painting. Apart from religious subjects, it occupied a special position in art specializing in the taste of the Court of Kyoto. Quails and Peacocks, cherry tree branches in flower, cocks and hens,

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

"Haiku shows us what we knew all the time,

but did not know we knew;

it shows us that we are poets

in so far as we live at all."

RH Blyth

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

A comment from Chen-ou Liu, Canada:

The idea explored in the quote is similar to that of Chinese painting method, "leaving blank” (liu bai in Chinese), with which artists may leave the background blank to enhance the impact in order to emphasize a particular subject.

This method is also widely applied to writing to explore the "silence" between the words/lines."

In his famous poem, Silence Is a Looking Bird, E. E. Cummings skillfully employed this technique to dive into the poetic realm -- silence ("some empty space along with an image") -- worthy of further exploration and even transgression of the boundaries of imagination.

Silence Is a Looking Bird

silence

.is

a

looking

bird:the

turn

ing;edge, of

life

(inquiry before snow

The following is an excerpt from my short essay on this poem, one that is relevant to our discussion:

The last line, “(inquiry before snow,” is left out a closing parenthesis and followed by a huge blank, loudly announcing a white downpour, a visual snow that covers the rest of the page. This literary device is similar to a Chinese painting method, "leaving blank” (liu bai in Chinese), with which artists may leave the background blank to enhance the impact in order to emphasize a particular subject. Silence is made visible on the page by the surrounding blank space. If silence is the unspoken by definition, through the reader’s imagination, silence can be experienced visually on the page. To some extent, this poem is not only textual but also visual, and Cummings skilfully enables the reader to decipher the mute hieroglyphs of the page and to turn them into speech. Silence is a looking bird, which can realize its potentiality of singing beautiful songs through imagination.

Chen-ou

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

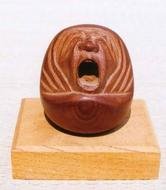

Two Daruma Dolls from Tosa, Shikoku

Daruma Pilgrims in Japan

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

3 comments:

ahhh.. yes, I keep that in mind with my photography as well as haiga.

Thanks for sharing!

.

.

Images of a Southern Utopia:

The Xiao and Xiang Rivers in Japanese Art

Seunghye Sun

Chinese Southern Song (1127-1279) and early Yuan (1271-1368) dynasty paintings were introduced in Japan around the late 13th century, and by the 14th century were already highly prized by the Ashikaga shogunate. Japanese patrons and painters particularly appreciated landscape paintings of the Xiao-Xiang area because most could not travel to China. Although some diplomatic delegations and Buddhist pilgrims were dispatched there, they were not able to journey to all of the mountains and rivers described in the poems on the Xiao and Xiang rivers, which lay far from the capitals they visited.

In China, in addition to representing the misty, spacious landscape of the south, this river area was associated with the image of a loyal and faithful spirit. We can also glimpse a Confucian connotation to the Xiao and Xiang rivers, which symbolize the unfair exile of a talented and faithful official by an unappreciative king or emperor, as narrated in the legend of Qu Yuan (c. 343-c. 277 BCE) and others. In Japan, however, this romantic vision of exile was not widespread as it was in China and Korea.

The Japanese were more fascinated by poetic and symbolic descriptions of nature than by laments of banishment, preferring to appreciate the eEight Views f as depicted in the unconventional style of ippin (lit., ethe untrammelled class f), a category of painting that exists in an ambiguous relationship with the orthodox sanpin, or ethree categories f. In its spontaneous depiction of natural phenomena, ippin can be compared to the enlightenment of Zen Buddhism. Japanese patrons used the metaphor to transform their daily living space into an idealized landscape by eliminating most of the motifs and retaining only the basic essence. On this point, the Japanese aesthetic differs from the Korean one in interpreting the eEight Views f imagery.

http://www.orientations.com.hk/php/latestissue.php?act=FEATURES&id=236

.

Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, Xiao-Xiang

Shooshoo Hakkei 瀟湘(しょうしょう)八景 (in Japanese)

MORE

Post a Comment